James Capper

Prototypes of Speculative Engineering

Musuem of Old and New Art 2021–2022

Co-curated with Jarrod Rawlins and Olivier Varenne

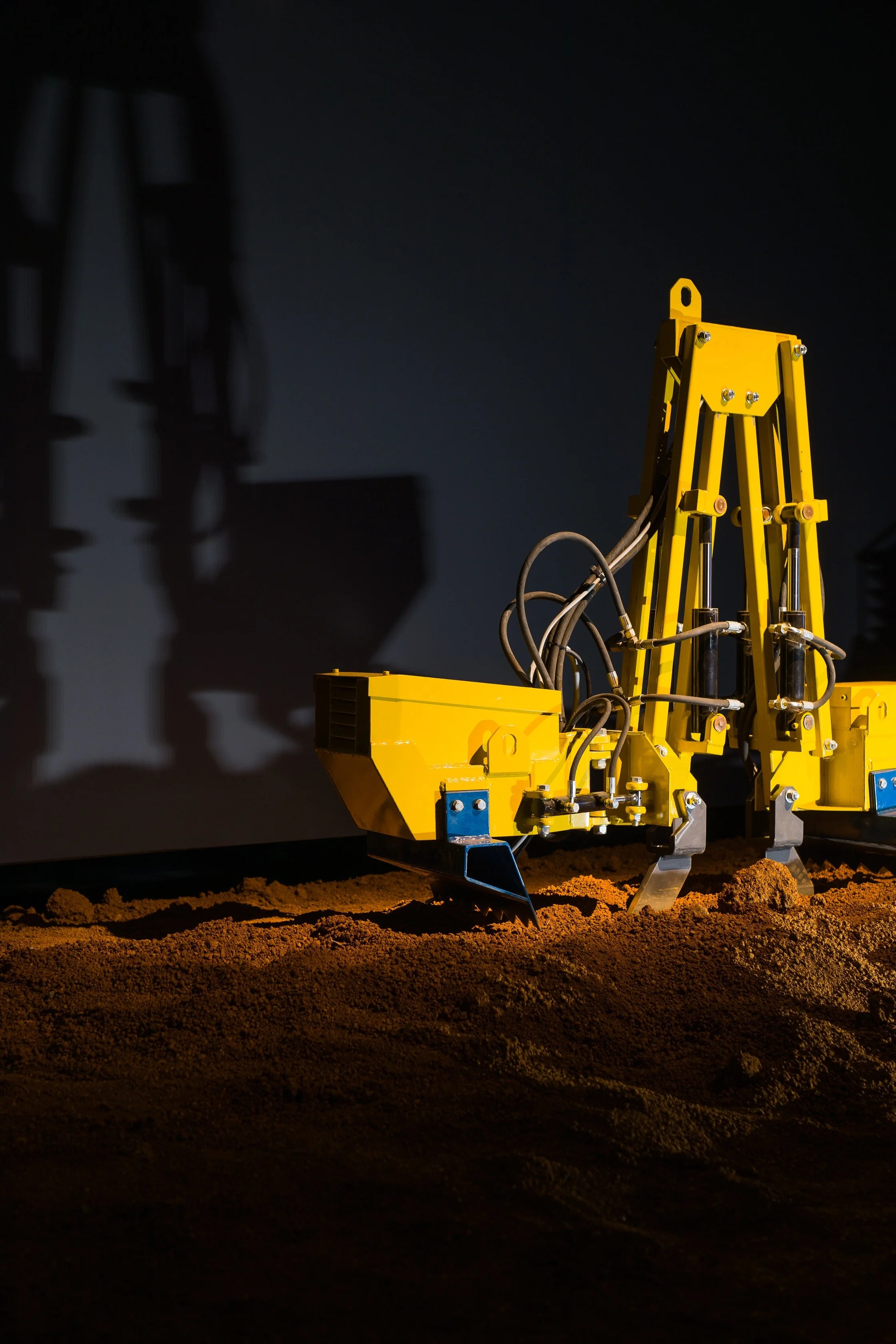

Deep underground: a red landscape transformed the gallery. There visitors found a pair of insect-like ‘mobile sculptures’ going about their mechanical choreography, digging and marking the earth.

Mechanical engineering, evolutionary science, and the long history of human technology harnessing biological innovation. Each plays a part in English artist James Capper’s work honing what sculpture can be and do, and exploring the relationship between art and ‘speculative engineering’: a leap into the unknown, beyond what engineering can currently do, in search of solutions to urgent problems of our time such as a changing planet. ‘In these solutions you will find my sculpture,’ says James.

Inspired by the movement of insects and evolution of vertebrae in walking species, James uses his ability as a steel fabricator and mobile hydraulics engineer to make sculptures that walk across landscapes. Their hydraulic systems hum into action, animated by complex problem-solving strategies and an artist driven not just to create but to understand.

And now to Broken Hill, Australia’s longest running mining town, where Capper’s sculptures navigated the outback—which visitors saw projected on the gallery wall and felt in the dirt beneath their feet—in a film made in collaboration with Australian filmmaker Alexander George. There is a landscape and community shaped by mineral extraction, confronting our chequered history of industrial innovation, and ultimately, the cost of progress and an uncertain future.

James draws inspiration from all over: from 450-million-year-old fossil footprints of creatures walking between freshwater pools in Western Australia, shedding light on how life transitioned out of the ocean and onto land; to Broken Hill’s cinematic terrain, from Mad Max to Wake in Fright; and even an ‘artificial cow’ that would carry food for an army on the move, built by Chinese commander Zhu Ge-Liang almost 1800 years ago.

Exhibition text by Luke Hortle